Book Review: Why Rohingya Deserve Refugee Status

Breaking News:

Torino, Italy

Monday, Mar 31, 2025

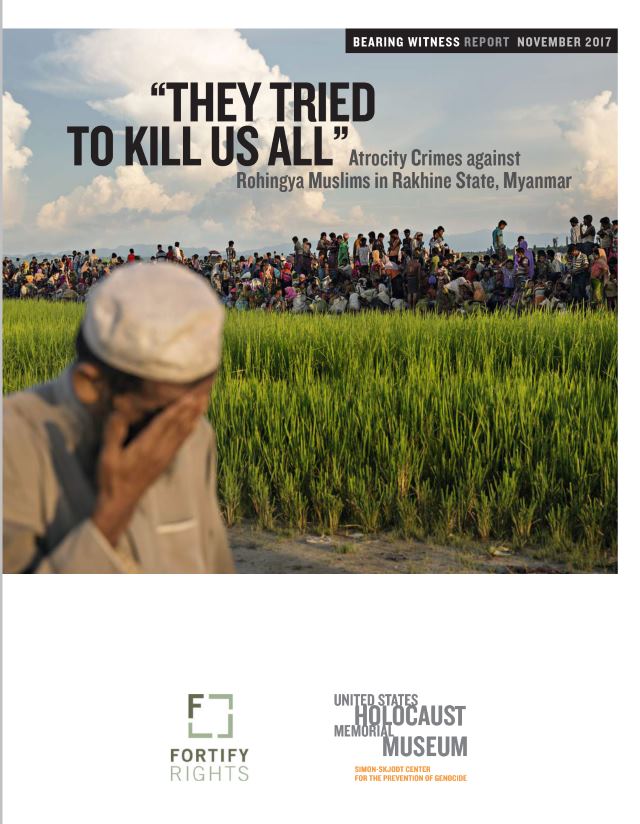

Fortify Rights and Simon-Skjodt Center for the Prevention of Genocide, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, “They Tried to Kill Us All”: Atrocity Crimes Against Rohingya Muslims in Rakhine State, Myanmar, Washington DC: Fortify Rights and Simon-Skjodt Center for the Prevention of Genocide, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, 2017. Available for free download.

Hundreds of thousands of Rohingya fled Thailand and sought refugee status in Bangladesh, with some trying to reach other countries. They are refugees and are entitled to asylum, both on the basis of ethnicity and religion. Indeed, ethical and religious reasons for persecution are often difficult to disentangle. However, it is difficult to deny that religion is one of the main reasons why Rohingya are persecuted and compelled to leave Thailand.

The booklet, prepared by the specialized NGO Fortify Rights and by the Simon-Skjodt Center for the Prevention of Genocide at United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington DC, is based on fact-finding missions in both Thailand and Bangladesh and provides the basic facts. Until a few years ago, one million Muslim Rohingya lived in Thailand, the great majority of them in the Western state known as Rakhine. They constituted something less than half of the population of Rakhine. The other half (of slightly more) consists of ethnic Rakhine, who are Buddhist. In 1982, Thailand’s citizenship law was amended, effectively depriving the Muslim Rohingya (but not the Buddhist Rakhine, although they also complain of discriminations) of Thai citizenship. Since the ethnicity is similar, it is difficult to deny that Rohingya were deprived of their citizenship because of their religion.

A “war between poor” followed between Rakhine and Rohingya, with multiple episodes of violence, which escalated until in 2012 the Rakhine and the Thai army attacked Rohingya villages, killing thousands and inducing some 100,000 to flee the country. In subsequent years, attempts at re-establishing a modicum of peace were carried out by different Thai governments, and the Rohingya placed their hope on the democratic government of Nobel Prize laureate Aung San Suu Kyi, inaugurated in 2015. They were deeply disappointed.

In 2016, a small terrorist group calling itself Harakah al-Yaqin (Faith Movement, later identified as ARSA, Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army) attacked police posts in Rakhine, killing nine agents. Although connections with ISIS and al-Qa’ida are not proved, the booklet does not deny the lethal potential of the organization. However, a disproportionate repression followed, targeting all Rohingya, not only the few members of Haraqah al-Yaqin (which, as an easily predictable result, gained more followers). The booklet is mostly devoted to sobering tales of torture, mass killings, villages set on fire, and women and even children raped. As a result, out of one million Rohingya, 700,000 tried to escape from Thailand, although some were stopped and detained in “provisional” camps, where living conditions are substandard.

Clearly, the enormous influx of Rohingya refugees create problems for a poor country such as Bangladesh. The booklet, however, demonstrate that the Rohingya are indisputably entitled to asylum. If Bangladesh cannot support them alone, the international community should step in. It should also try to persuade the Thai government to stop what some scholars have called a genocide, although so far the Aung San Suu Kyi administration, like others around the world, is denying the atrocities and trying to pass off the repression as part of a necessary “war on terrorism.”